Oisin Clark lives at number 2, Nether Oak Close. This fact has not changed, despite everything else doing so. His father died six months ago.

By most outward measures, Oisin has done grief properly. He has moved through the stages as defined by Elisabeth Kübler‑Ross, shock, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, though never in that order, and rarely one at a time. If there were certificates handed out, he suspects he would have earned one. What remains now is a sense of emptiness that arrives without warning, with tears never far behind it. Six months, he has learned, is both a long time and no time at all.

Some things have changed. Others stubbornly have not. His father’s mug, the chipped one with the faded joke “Teachers do not die, they just lose their class”, still sits at the back of the cupboard. Oisin neither uses it nor throws it away. It occupies its space like a truce neither side wishes to test.

The dog needs walking regardless. Grief, Oisin has discovered, does not exempt anyone from routine, least of all dogs.

That afternoon the park is ordinary in the way parks usually are, damp grass, tired benches, the distant sound of a child laughing and immediately falling over and crying for “Muuuuuuuum!”. Oisin walks without much attention to where he is going, letting the dog set the pace. Halfway around the loop, the dog stops.

This is unusual.

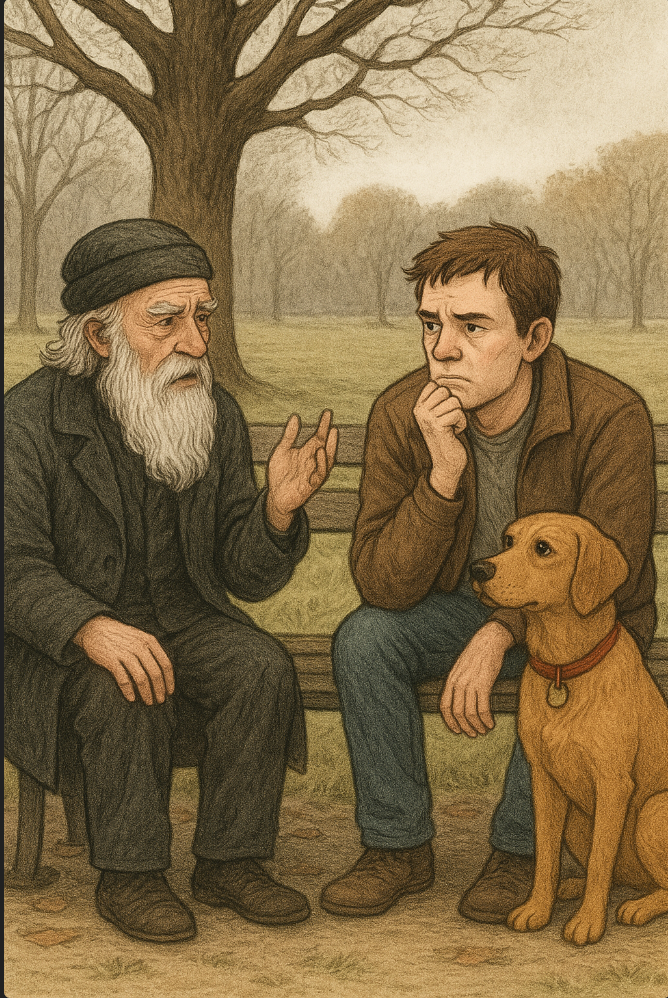

Normally, it ignores strangers with polite indifference. Today, however, it plants its feet and leans into the outstretched hand of an old man sitting on a bench, allowing itself to be patted with the solemn concentration of a creature convinced this is exactly what it was born to do.

“Well,” Oisin says, more to the dog than the man, “you’re clearly making friends without me.”

The man looks up and smiles, as if he has been expecting precisely this moment and no other. He is slight, wrapped in a coat that seems older than fashion, his hair white and unruly. His eyes are sharp, amused.

“She knows,” he says, his accent thick, unfamiliar. “Dogs often do.”

Oisin shrugs. “That makes one of you.”

The man chuckles, a sound like gravel poured gently into cloth. “Most people do just not when alive.” He pauses, then adds, “I am called Ogmios.”

“Oisin,” he replies, after a moment. “And apparently this is my dog.”

“Aww‑sheen,” Ogmios says, tasting the name. “Names were heavier in my day. You could stub a toe on them.”

Oisin smiles despite himself and sits at the far end of the bench. The dog settles between them, paws on Oisin’s knee, content, having clearly chosen sides.

“I have a side occupation,” Ogmios continues, scratching behind the dog’s ears. “I am tasked with looking after human Eloquence, mostly. And when required, I guide the dead from one place to another.”

Oisin considers this. He has found that agreeing with strange statements is often the quickest way through them. “Of course you do.”

Ogmios turns to him. “Tell me,” he says gently, “what is it that troubles you?”

The question lands without force, without expectation. Oisin immediately distrusts this. Questions are rarely so polite.

He exhales anyway. “My father died,” he says. “Six months ago. He was… central. And I thought by now things would feel normal again.”

Ogmios laughs, not unkindly, though there is a hint of delight in it, as if Oisin has stepped exactly where the path intended. “Normal,” he repeats. “I have known millions of souls, and not one of them would answer to that name. Life has only the faintest outline of what it intends to be. Most days it wanders off, distracted by a pretty flower,a squirrel in a tree, or the death of a father, and becomes something else entirely. Still ordinary. Just ordinary with an extraordinary shine”

Oisin looks down. The dog sighs and presses its weight more firmly against him, a small but decisive vote of confidence.

“The dead,” Ogmios says, more softly now, “are never finished with the living. They move quietly through them, borrowing breath and memory, shaping what remains. Someday you will join them, not as a loss, but as a weight added to the world. A pressure that makes each moment matter.”

Oisin looks up, then around the park, checking, briefly and without much hope, for hidden cameras, dramatic lighting, or any other sign that this is not a perfectly normal afternoon gone somewhat weirdly wrong.

He does not feel a revelation so much as a disturbance. An idea settling where it has not been invited. He thinks of his father, foremost among a crowd. Not watching. Not judging. Simply present, as soil is present around the roots of a tree. Every step he has taken has been crowded with footsteps that ended before his own. The thought is unsettling. It is also, annoyingly, comforting.

Ogmios tilts his head. “What endures is not the pain, but the fact that it was earned. To have been changed is not a failure of survival. It is its own evidence.”

Oisin is silent for a long time and Ogmios reaches in his pocket and takes out a half eaten cheese sandwich, which is pulls apart and scatters on the grass infront of the bench. Two large ravens, feathers Iridescent in the afternoon sun flutter down from a nearby tree. Ogmios nodded at them and one stopped pecking and nodded back.

Oisin understands, or at least suspects, that he will not last, and that this will not be an erasure. He is not entirely convinced. Still, the idea lodges itself stubbornly in his chest, refusing to be dismissed.

He stands. The dog licks Ogmios’ outstretched hand with the easy familiarity of someone saying goodbye to an old friend.

“Thank you,” Oisin says, uncertain exactly what he is thanking him for.

Ogmios inclines his head.

Oisin walks out of the park and home, to continue his life. Nothing has been resolved. His father is still dead. Tomorrow will still arrive. But the path feels wider than it did an hour ago, and that, for now, is enough, his journey continues.