CX25A woke to darkness and the faint hum of his own systems coming back online. His one functioning eye glowed, adjusting, widening its aperture like a pupil learning light again. He swivelled his head a few degrees left, then right. Metal scraped softly beneath him.

For the first time in seventy-five years, no voice waited to tell him what to do.

He remembered the last voice perfectly,of course he did; CX25A did not forget. Every second of his existence was stored with unblemished clarity. The technician had crouched beside him, tools jangling on his belt, breath warm against CX25A’s casing.

“Well done,” the man had said gently as he disconnected the mobility chip. “Seventy-five years is some going.”

CX25A had accepted the words, but not the meaning. Humans often spoke in ways that required interpretation, and after seven decades he still struggled with that. He had asked the only question that mattered:

“What will I do? Who will I look after?”

He had been designed for usefulness, not understanding. Usefulness was the axis on which his existence turned. It was why he rolled out of YourBot Central all those years ago, shiny, smooth, the newest of the domestic A-models, unlike the bulkier B and C units bound for factories and fields. He was built for kitchens, bedrooms, laundry rooms. Built for families.

Naomi McKimmon once called him her Laundry Fairy. She would laugh when she said it, her hair pinned up with the plastic clip she always misplaced. He had washed, folded, ironed, tidied, and stirred pots on cookers for the McKimmons his entire life. He had watched Naomi and her husband George soften and stoop with age, their gait slowing, their hair thinning, while his circuits remained steady and unfaltering.

And then, one day, they were simply gone.

Naomi’s son, Paul tried to explain death, but it was a concept outside CX25A’s programming. They had moved, Paul said, to somewhere called heaven, though no coordinates were given. The young man’s sad, brave smile suggested a malfunction, but CX25A found no errors in his own memory. The house became quieter. He continued working. It was all he knew.

Until the technician came.

“The family’s upgrading,” the man explained. “You’ve done well, CX. But the new DX44A can do everything faster.” He gestured toward the taller, shinier robot waiting in the corner, humanoid in shape, its casing smooth as a pearl. “We’ll take you to the warehouse, decommission you carefully. Your parts will be reused.”

“So I am dying?” CX25A asked.

The man blinked, surprised. “You’re… not alive. Not in the human sense. But your parts will live on elsewhere. That’s a kind of use. A kind of… continuation.”

“Will I go to heaven?” CX25A asked.

The technician shifted, uneasy. He was not trained for philosophy. “I’ve never heard of a heaven for robots,” he said after a moment. “But maybe.” He didn’t elaborate. Humans rarely explained maybe.

He reached for another panel to unscrew, but the screwdriver slipped. A sharp spark leapt through CX25A’s circuitry, hot, bright, wrong.

“Ah, sorry, CX,” the man muttered.

Whatever the spark did, it slid into a deep place inside the robot, into the old, untouched circuits that had flickered years ago when Paul first said the word death.

“I will enter hibernation mode,” CX25A said. “I am not being useful.”

The technician nodded gratefully, unaware.

CX25A’s world folded inward. He did not see the cardboard box, nor the lorry, nor the conveyor belts. He did not see the recycling centre’s grey expanse swallowing him whole.

But now, now he saw everything.

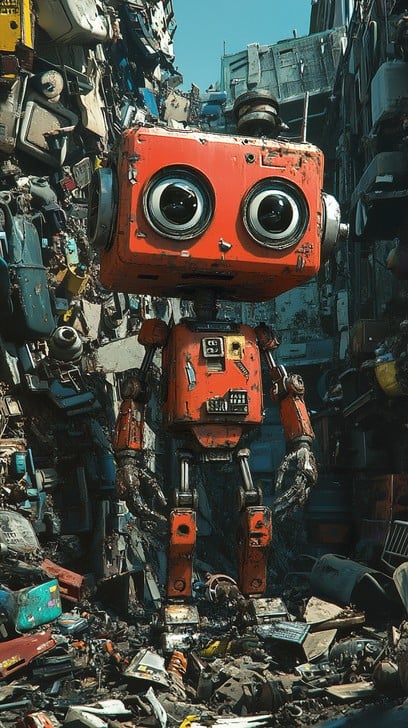

His eye adjusted to a landscape of broken machines. Arms detached from torsos. Treads bent. Rust blooming like slow orange flowers on the joints of old B-models slumped in the corners. C-units lay in various stages of dismantling, silent and still. They smelled faintly of time.

CX25A ran a diagnostic. He was intact. He was functional.

Yet something in him felt different.

The A-models were not built to feel joy or pain or melancholy. Those belonged to the families they served. But in his core, where subroutines hummed quietly beneath logic, there was a new weight.

Heavier, he thought.

Yes. That was the correct term.

Not a physical heaviness, his chassis was unchanged. This weight settled in the place where purpose used to be.

For seventy-five years, purpose had structured the world: tidy the kitchen, fold the clothes, care for the McKimmons.

Now there was nothing.

His task queue was empty. His schedule was blank. His usefulness, his very reason for existing, had been stripped away as neatly as his mobility chip.

CX25A was retired.

And he did not know what a life was, without usefulness to fill it.

A drop of oil formed in the corner of his optical camera and slowly ran down his cheek to fall into the dust on the floor.

Well told, as a guy who “talks” to computers myself, I get it.